No Doves in the Holy City

Collapse of ethics and the theatre of war—from the daughter of a child soldier.

“The true hero, the true subject, the centre of the Iliad is force. Force employed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man’s flesh shrinks away.

To define force— it is that x that turns anybody who is

subjected to it as a thing. Exercised to the limit, it turns

man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a

corpse out of him. Somebody was here, and the next minute

There is nobody here at all; this is a spectacle that the Iliad

never wearies of showing us:

. . . the horses

Rattled the empty chariots through the files of battle,

Longing for their noble drivers. But they are on the

ground

Lay, dearer to the vultures than to their wives.

The hero becomes a thing dragged behind a chariot in

The dust:

All around, his black hair

' Was spread; in the dust his whole head lay,

That once-charming head; now Zeus had let his

enemies

Defile it on his native soil.

The bitterness of such a spectacle is offered us absolutely”

THE ILIAD

Or, The Poem of Force

by Simone Weil

Translated by Mary McCarthy

War has never been a domain of morality. It is a theatre where ethics collapse the moment violence erupts and what follows is not principled restraint, but strategic necessity cloaked in moral language. This essay contends that wartime moral appeals are not genuine ethical arguments but performative acts designed for optics, survival, and the containment of public sentiment. Morality in war does not prevent or resolve conflict; rather, it is a tool wielded post facto to justify actions already taken, to frame narratives, and to pacify populations. The ethical frameworks that govern civil society falter under the brutal realities of war, replaced by a ritualistic performance of morality that masks the strategic and often brutal calculus of power.

This is not an essay about right or wrong in war, nor a moral judgement of any side in any conflict. Instead, it is an investigation into how and why morality becomes a language of theatre in wartime, a mechanism of political and psychological control rather than a genuine arbiter of justice. The invocation of human rights, just war theory, and international law often serves less to govern conduct than to manufacture legitimacy and rally domestic or international support. It is this dissonance—the chasm between moral rhetoric and military reality—that this essay explores.

By understanding morality as an instrument rather than a guide in wartime, we can move beyond sentimental illusions and begin to grasp the structural realities that govern violent conflict. The objective here is to dissect the performative nature of wartime ethics, reveal their limitations, and challenge the comfortable narratives that enable perpetual strife. If war signals the failure of ethics, then moral appeals during war are symptoms of denial, not solutions. Only through clear-eyed intellectual honesty can we hope to confront this truth and begin to rebuild the ethical foundations that prevent war, rather than futilely invoke them after the fact.

Function of Ethics in Peacetime Versus Wartime

In times of peace, ethics serve as the bedrock of civil society. They regulate behaviour, establish boundaries of acceptable conduct, and provide frameworks for resolving disputes without violence. Ethical systems—rooted in shared values and norms—guide individuals and institutions toward cooperation, justice, and mutual respect. They create a social contract that balances interests and enforces rules through law and culture. Ethics in peacetime function as proactive mechanisms; they aim to prevent harm by fostering order and predictability. Through dialogue, compromise, and accountability, society maintains cohesion, even amid disagreements.

However, when war erupts, this delicate ethical framework fractures. The transition from peace to conflict marks a rupture where moral principles no longer dictate behaviour in the usual sense. War is a realm where survival, power, and strategic calculation overshadow the rule of law and ethical consistency. The ideals that hold society together—justice, fairness, respect for human life—are suspended or selectively applied. Instead of regulating behaviour, ethics become reactive and symbolic, often invoked only to justify actions already taken or to shape public perception after the fact.

This shift is neither accidental nor temporary; it reveals a fundamental contradiction between the ethics of peace and the realities of war. Ethical systems demand fairness and restraint, yet war thrives on asymmetry, coercion, and the exertion of overwhelming force. The very nature of war—its violence and uncertainty—breaks the conditions necessary for ethics to operate as genuine constraints. When one side views the other as an existential threat, moral boundaries blur, replaced by pragmatic decisions that prioritise victory over principle.

Ethics in wartime transform into a performative act, a ritual designed less to guide action than to contain its consequences. The language of morality becomes a tool for managing the psychological and political fallout of violence rather than a guide for ethical conduct. Governments and leaders use moral rhetoric to justify military campaigns, rally domestic support, and maintain legitimacy on the world stage. The invocation of just war theory, human rights, or international law is often post hoc—a veneer applied to retrospectively rationalise decisions driven by strategic interests.

Moreover, the public, distanced from the battlefield, consumes these moral narratives as a way to reconcile the horrors of war with their sense of justice and humanity. The ritual of moral appeals functions as a psychological salve, offering reassurance that violence is necessary and justified, not arbitrary or unjust. This dynamic sustains political support and dampens dissent, even when the conduct of war contradicts professed ethical standards.

In sum, the function of ethics in wartime is fundamentally different from its role in peacetime. Far from being proactive guides that shape conduct, wartime ethics are reactive performances aimed at framing violence within acceptable narratives. This transformation reflects the collapse of ethical coherence when confronted with the brutal realities of conflict. Understanding this distinction is crucial to grasping why moral appeals during war often ring hollow and fail to influence the course of violence.

Performance of Moral Rhetoric in War

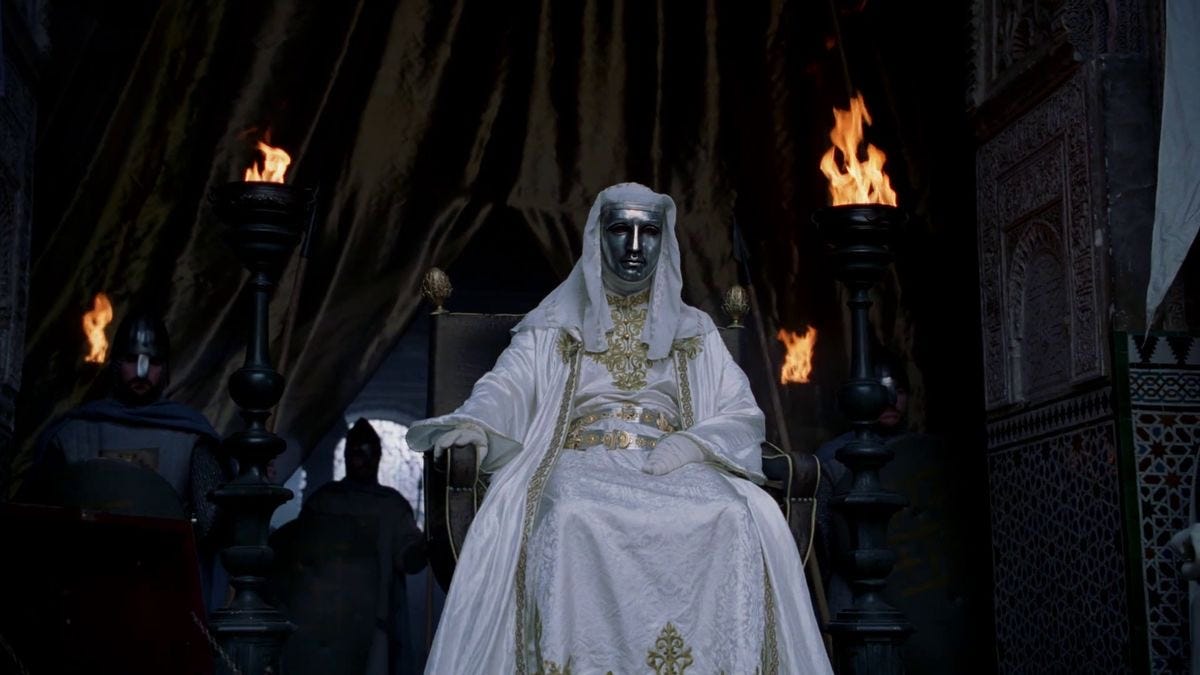

Once war begins, moral language no longer operates as a binding force on action—it becomes performance. This is not morality as a compass, but morality as a costume, worn to narrate violence in palatable terms. Governments, military leaders, and media all participate in this theatre of righteousness. Appeals to justice, legality, or humanity do not usually precede action; they follow it. The decisions—bombings, invasions, assassinations—are made first. The ethical justification is crafted after the fact, shaped to match political objectives and manage public response.

The clearest symptom of this is the ubiquity of slogans in modern warfare: “right to defend,” “collateral damage,” “proportional response,” “never again.” These phrases do not describe the event—they narrate it, condition it, contain it. They help construct a script in which violence appears tragic but necessary, restrained rather than barbaric. It is not the war itself that is being judged, but the story told about the war. Leaders do not seek moral clarity—they seek moral credibility.

Take, for example, the selective invocation of “human rights.” This concept, noble in its universalism, becomes fractured in wartime. Violations are highlighted only when politically convenient. Civilian casualties are tragic when suffered by allies, incidental when inflicted by them. War crimes are prosecuted by the victors, not the perpetrators. Morality becomes less a standard and more a cudgel—used to condemn enemies, justify allies, and distract domestic populations from the ethical contradictions inherent in military action.

In this context, the role of the media is not to question but to transmit. Even the most critical outlets are constrained by national interest, audience appetite, and access to information. They participate in the moral spectacle, not as impartial observers but as a chorus. Stories are curated. Images are chosen for their emotional impact, and interviews are framed to maintain a moral narrative. While some journalists do interrogate official accounts, the overall structure reinforces the performance rather than breaking it.

This performative use of ethics is not merely cynical—it is necessary in liberal democracies. Democracies cannot sustain mass violence without the appearance of moral legitimacy. The electorate must be reassured that their nation is not only powerful but righteous. And so, the language of morality is co-opted into a national mythos: “we do not start wars, we respond”; “we do not target civilians, we mourn them.” This language doesn’t stop war—it sustains it by keeping dissent fragmented and conscience soothed.

Importantly, this moral theatre also distances the public from the true nature of war. By packaging violence in the language of rights, justice, and self-defence, the public is spared the cognitive dissonance of supporting organised killing. It allows individuals to align with power without the psychological cost of complicity. In essence, moral performance enables democratic societies to maintain both war and their self-image of ethical superiority.

Thus, wartime morality operates not as a shield but as a script. It creates the illusion that ethics still govern the battlefield when in reality, they govern only the narrative. This narrative is not neutral; it is a strategic asset. It ensures that war is not only fought—but felt—in ways that protect political legitimacy and social cohesion. Understanding this reveals the futility of treating wartime ethics as sincere attempts at moral arbitration. They are, overwhelmingly, theatre.

Selective Justice & the Self-Definition of War Crimes

If morality in wartime is theatrical, then justice is its costume department—dressing each act of violence in the garb of legitimacy or condemnation depending on the actor. The term “war crime” is often treated as a universal moral category, implying shared standards and clear lines. In reality, war crimes are overwhelmingly politically defined. They are prosecuted selectively, condemned inconsistently, and weaponised rhetorically. The same act—targeting civilian infrastructure, for instance—can be labelled as criminal atrocity in one context and strategic necessity in another, depending solely on who commits it and how they narrate it.

This is not to suggest that atrocities aren’t real or horrific. Rather, it is to highlight that their framing is contingent. International law, while noble in conception, functions unevenly in practice. Great powers seldom face accountability. Allied nations shield one another. Meanwhile, weaker or adversarial states become the primary subjects of tribunals and investigations. What this reveals is that the moral framework applied to war is not truly global—it is hierarchical, contingent, and self-referential.

Consider how different conflicts are remembered. The firebombing of Dresden, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the razing of Fallujah, the siege of Grozny—each left thousands of civilians dead, and yet none are uniformly remembered as war crimes. They are discussed as strategic, necessary, or even heroic. Conversely, similar acts by weaker states or non-state actors are swiftly condemned as barbaric, lawless, or genocidal. This is not a difference in severity, but in narrative power. It reflects the uncomfortable truth that war crimes are not absolute—they are decided in the court of global perception, not necessarily in The Hague.

This self-defining logic also appears internally. Nations tend to define their conduct as defensive and morally just, even when committing acts indistinguishable from those they condemn. For instance, one side’s “collateral damage” is the other’s “massacre.” One side’s “surgical strike” is the other’s “ethnic cleansing.” These terms do not describe the act—they shape how it is understood. They filter reality through a lens that aligns with the speaker’s moral identity and geopolitical interests.

The result is a double bind for observers and participants alike. To challenge the moral legitimacy of one side is often seen as an implicit endorsement of its enemy. This binary moral framing flattens complex conflicts into simplistic narratives: good versus evil, just versus unjust. It leaves no room for acknowledging mutual brutality, contradictory motives, or the shared degradation that war inflicts on all participants. The moral language used becomes a form of control—both of external interpretation and internal dissent.

Selective justice erodes the credibility of international ethical norms. If moral standards are only enforced against the weak, they cease to function as standards at all. They become instruments of soft power—tools to isolate enemies, justify sanctions, or retroactively validate intervention. This dynamic produces widespread cynicism. People begin to see moral language as camouflage for strategic intent. They grow disillusioned, not because they are apathetic, but because they sense that the rules are rigged.

Yet perhaps the deepest implication of this moral selectivity is existential. If each side defines justice according to its self-interest, then the very notion of war crimes becomes tautological. A war crime is what your enemy does. What you do is necessary, unfortunate, or righteous. This logic renders the moral terrain of war completely relative—each actor fighting not only for survival, but for control over the narrative of who was right. In this space, there are no referees, only players with louder microphones and better optics.

In sum, the concept of justice in war is not a neutral adjudicator—it is a contested weapon. It functions less as an objective moral barometer than as a narrative currency. To understand this is not to surrender to moral relativism, but to confront how deeply entangled justice has become with power. In war, to be just is not to act differently—it is to tell the better story.

Political Instrumentalisation of Morality

The use of moral rhetoric in warfare is rarely aimed at actual ethical reflection—it is overwhelmingly instrumental. Political leaders deploy the language of rights, law, and justice not because these values guide their decision-making, but because they are effective tools of persuasion, legitimation, and control. In this sense, morality in war is less a compass than a weapon—a strategic asset used to frame actions, consolidate public support, and delegitimise opponents. This instrumentalisation is so embedded in contemporary political communication that even the most brutal acts are often couched in the vocabulary of humanitarianism.

Consider the way humanitarian interventions are marketed. Phrases like “protecting civilians,” “restoring democracy,” or “preventing genocide” are routinely invoked to justify military campaigns, even when their underlying motives are geopolitical. The 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the 2011 intervention in Libya were all framed as moral imperatives. Yet in each case, the aftermath revealed more about power and chaos than about the success of ethical intentions. What mattered politically was not the outcomes, but the pretext—the moral optics required to sell war to domestic and international audiences.

This rhetorical sleight of hand also operates internally. Governments speak in the language of morality to frame dissent as treason and protest as unpatriotic. When moral legitimacy is attached to the state’s actions, those who question them are not merely political opponents—they are portrayed as immoral, dangerous, or complicit with the enemy. The moralisation of war thus becomes a way of insulating power from criticism. It allows leaders to act unethically while branding their critics as unethical. The result is a chilling environment in which ethical language is used to suppress ethical thought.

Moreover, this phenomenon is not confined to autocratic regimes. Liberal democracies are often the most adept at using moral framing to justify war, precisely because they must win over public opinion. In societies where violence cannot be justified through divine right or sheer force, it must be clothed in the robes of humanitarian necessity. This produces a peculiar dynamic in which the more power claims to act ethically, the more cynical its actions often become. The gap between moral language and material reality widens until the words themselves begin to hollow out.

Instrumental morality also creates strategic liabilities. When leaders base their military actions on moral claims, they lock themselves into narratives that are difficult to maintain. Every civilian death becomes a potential scandal. Every deviation from the “just war” script risks political backlash. The result is not more ethical warfare, but more sophisticated propaganda. Drone strikes are renamed “precision targeting.” Detention without trial becomes “enhanced security.” Torture is rebranded as “enhanced interrogation.” Language is bent to fit the strategic need, even as it appears to uphold ethical norms.

Perhaps most corrosive is the way this instrumentalisation feeds into public exhaustion. When people witness the endless cycle of moral posturing followed by moral failure, they begin to disengage. They stop believing in justice not because they reject it in principle, but because they see how it is used in practice. The moral language of war becomes background noise—a kind of whitewash applied to every atrocity, until nothing seems real, and everything feels staged.

Ultimately, the political use of moral rhetoric in war does not elevate ethics—it evacuates them. It reduces complex human suffering to a soundbite. It converts principles into tools of manipulation. And it erodes the very foundations of public trust, replacing deliberation with emotional coercion. What remains is a hollow theatre in which morality performs, but never acts.

Ethical Bankruptcy in Public Discourse

The constant, often contradictory use of moral language in modern war has led to a kind of ethical bankruptcy in public discourse. Terms that once held immense gravity—genocide, fascism, war crime—are now deployed so casually and so frequently that they begin to lose meaning. This rhetorical inflation does not clarify conflicts; it distorts them. It turns war into a battleground not just of bullets and bombs, but of competing moral claims, each louder and more emotionally charged than the last.

This saturation point has produced a strange paradox. On the one hand, war discourse is more moralised than ever. Social media, news cycles, and state press briefings all pulse with righteous indignation and moral appeals. On the other hand, the public is more disillusioned, detached, and fatigued. The more we are told that a war is “just,” the less we seem to believe it. The result is a widespread emotional numbness, as if we are watching a play whose lines we know by heart—and no longer find convincing.

This erosion of meaning is not accidental. It is a function of repetition without reflection. When every civilian casualty is framed as a tragedy—but only when it serves a geopolitical narrative—the public begins to detect the pattern. When justice is invoked only to punish enemies, and not to restrain allies, people intuit the game being played. The effect is not just political; it is existential. It breeds a form of spiritual exhaustion, a hollowing out of belief in shared values or common humanity.

The media plays a central role in this collapse. Driven by outrage and virality, headlines reduce complex conflicts to moral binaries: aggressor and victim, evil and good. Context is sacrificed for clarity. Ambiguity is banished. Yet war is inherently ambiguous. It is full of competing truths, contradictory imperatives, and irreconcilable grievances. To speak of it as a morality play is to misrepresent its structure. But it is also to comfort an audience that demands coherence, even if it must be manufactured.

Activism is not immune to this pattern. The moral hyperinflation of online discourse has transformed many political causes into brands of outrage. The focus shifts from outcomes to optics. “Raising awareness” becomes the end in itself, rather than a step toward meaningful change. Protests are evaluated by their aesthetic impact, not their strategic effect. And as a result, serious moral inquiry gives way to performance—anger without action, slogans without policy.

This ethical void poses real dangers. When moral language is used cheaply, it becomes easier for genuinely immoral acts to hide in plain sight. When everything is a war crime, nothing is. When every enemy is genocidal, the concept of genocide becomes diluted. This blurring of boundaries makes it harder to hold anyone accountable. It invites bad faith actors to mimic the language of justice while pursuing naked self-interest. And it disorients ordinary people who are trying to navigate truth in an environment of perpetual outrage.

The collapse of ethical coherence in wartime discourse reflects a broader cultural fatigue. We are not suffering from a lack of moral frameworks—we are suffering from a glut of them, piled atop each other, unexamined, and wielded strategically. The task ahead is not to amplify moral noise, but to reconstruct moral meaning. That can only happen through honesty, restraint, and a commitment to complexity over clarity.

Case Studies in the Illusion of Moral Consistency

Examining specific conflicts reveals how wartime moral rhetoric functions less as a guide to justice and more as a strategic instrument shaped by political interests and narrative control. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict exemplifies this dynamic. Both parties invoke moral frameworks to justify their actions: Israel frames its military operations as existential self-defence rooted in historical persecution and national survival, while Palestinians articulate their resistance through the language of anti-colonial struggle and human rights. These moral appeals do not neutralise the conflict but instead reinforce entrenched positions and mobilise domestic and international support. Each side’s ethics serve strategic ends rather than universal principles, highlighting the instrumentalisation of morality in wartime.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan further illustrates the selective application of moral reasoning. Both states claim legitimacy based on sovereignty, historical ties, and ethnic identity, while each accuses the other of aggression and human rights violations. Global responses often reflect geopolitical alliances rather than consistent ethical scrutiny, revealing the contingent nature of moral outrage in war. The competing narratives expose the performative character of moral appeals, which are tailored to justify violence and secure political advantage.

In South Asia, the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan similarly demonstrates how moral claims are embedded within nationalistic projects. India portrays its actions as maintaining territorial integrity and combating terrorism, framing itself as a guarantor of secular democracy. Pakistan, meanwhile, positions itself as a protector of the Muslim population and critic of perceived oppression. Both narratives employ moral language strategically to validate policies and influence international opinion. The conflict’s complex reality—marked by military presence, civil unrest, and human rights concerns—is obscured by these competing ethical performances, which serve more to sustain the conflict than to resolve it.

Sudan’s internal conflicts reveal how systemic violence and demographic engineering are rationalised through shifting moral narratives. Various armed groups and government forces have engaged in campaigns targeting ethnic communities, resulting in mass displacement and allegations of ethnic cleansing. These actions are justified through appeals to national security, historical grievances, or political survival. International responses have fluctuated, influenced by geopolitical interests and the difficulty of applying universal moral standards in complex civil wars. This underscores how ethics in war become malleable tools shaped by context, not fixed principles.

These case studies collectively demonstrate the selective, contingent, and performative nature of wartime morality. Moral appeals are less about universal justice and more about framing violence to maintain legitimacy, mobilise support, and discredit opponents. This strategic use of ethics contributes to the endurance of conflict by masking the underlying realities of power and survival. Ultimately, they reveal that wartime morality is not a consistent code but a fluid rhetoric adapted to political needs.

Toward Intellectual Honesty and Stronger Ethical Foundations

Recognising the collapse and manipulation of ethics during war compels us to reconsider how societies engage with the concept of morality in conflict. Rather than clinging to the illusion that ethical appeals can meaningfully restrain violence once war has erupted, a more honest approach acknowledges the limits of wartime morality. The ethical frameworks that govern peaceful civil life cannot simply be suspended and then expected to function mid-conflict. Attempting to salvage morality after violence has already begun is often a performative exercise that obscures strategic realities and prolongs suffering.

True progress requires building robust ethical institutions and political structures in times of peace that anticipate and mitigate the descent into conflict. This includes transparent diplomacy, conflict resolution mechanisms, and education that fosters critical engagement with power and violence. It also demands confronting uncomfortable truths about how political interests shape moral narratives and public perceptions. Only by grounding ethical discourse in historical, political, and strategic realities can societies hope to develop frameworks that meaningfully reduce the frequency and brutality of war.

Moreover, fostering intellectual honesty means resisting the temptation to moralise conflicts in simplistic terms or to weaponise ethics as propaganda. It involves acknowledging that all actors in war operate within a system where survival, power, and pragmatic considerations often overshadow abstract ideals. This perspective does not excuse atrocities or diminish human suffering; rather, it situates these events within a realist understanding of war’s nature—one that prioritises clarity over sentimentality.

By confronting the limitations of wartime morality and focusing on pre-war ethical resilience, we may begin to shift public consciousness away from performative outrage toward constructive engagement. This transition requires courage, critical thinking, and a willingness to dismantle comforting myths about justice in war. It also challenges leaders, intellectuals, and citizens alike to take responsibility for cultivating peace through practical means, rather than relying on post-hoc moral posturing.

In essence, the future of ethical political discourse depends on accepting that morality in war is not a salvageable ideal but a symptom of broader structural failure. The solution lies not in debating who holds the moral high ground once conflict erupts but in fortifying societies against the conditions that make such conflicts inevitable. Only through this sober, realistic, and forward-thinking approach can we hope to transform the tragic theatre of wartime morality into a foundation for lasting peace.